Ruthless Cosmopolitans

James Boswell knew that the first qualification for being friends with a great writer is a thick skin. In his biography of Samuel Johnson, Boswell writes that the first time he met his literary idol, Johnson mocked him for being Scottish. The young man swallowed the insult: “Had not my ardour been uncommonly strong, and my resolution uncommonly persevering,” he admitted, “so rough a reception might have deterred me for ever from making any further attempts.”

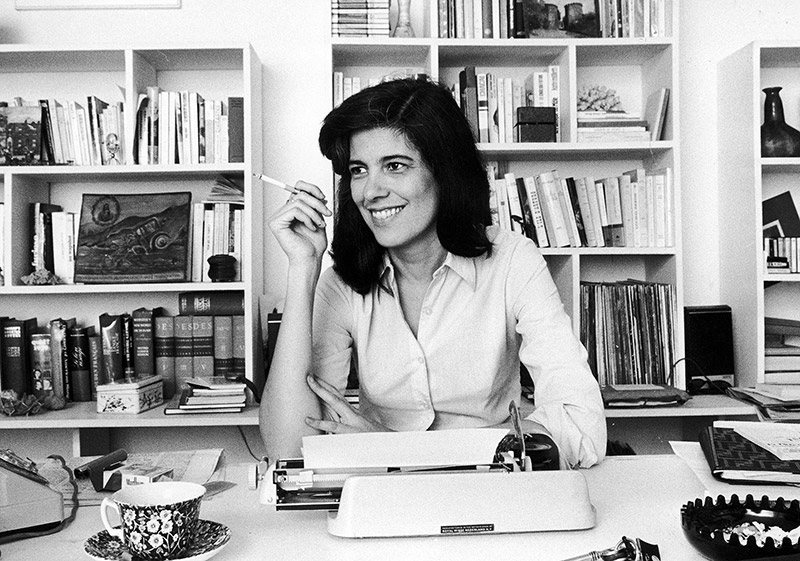

As the longtime editor of Salmagundi, the estimable intellectual quarterly, Robert Boyers has had the opportunity to befriend a number of his literary idols, and although he hasn’t been put off by their bad behavior, the title of his new memoir, Maestros & Monsters, suggests a certain ambivalence. The book focuses in particular on two writers who, like Dr. Johnson, achieved fame as critics and essayists. Susan Sontag, born in 1933, and George Steiner, born in 1929, had much in common. Both were omnivorous Jewish intellectuals who seemed to have read everything, loved fighting about ideas, and made it their mission to introduce difficult European writers to American readers.

They also both came in for more than their share of hostility and envy. Boyers begins his memoir by quoting Emerson’s “Nothing is got for nothing,” suggesting that the enmity of lesser minds was the price Sontag and Steiner paid for being geniuses. He especially admires their sheer passion for literature, praising Sontag’s “obsessive, excitable, insatiable” love of writers and Steiner’s “palpable and irresistible” excitement when explicating a text.

But Boyers also seems to be quoting Emerson as a reminder to himself. Nothing is got for nothing, but when it came to these friendships, did he give too much and receive too little? Now that his friends are gone—Sontag died in 2004, Steiner in 2020—Maestros & Monsters is his attempt to draw a balance sheet on these relationships, which provided intellectual stimulation and prestige but also humiliation and resentment, amply chronicled in the book. Boyers writes that he “would spend occasional sleepless nights” thinking about Sontag, “tallying her virtues and hopelessly measuring them against her unbecoming qualities.” The relationships were able to last so long because he always concluded that the good in his friends outweighed the bad: “As our friendship deepened,” Boyers writes of Steiner, “I came to regard as incidental what was harsh or ungenerous in him.”

Steiner comes across as the less difficult of the two, because his rudeness was usually directed against peers and rivals. Boyers was present on one occasion when he refused to be introduced to Edward Said, announcing “I do not shake hands with scum,” because Said had given him a mixed review. Sontag, on the other hand, seems to have been ready to blow up at anyone who rubbed her the wrong way, from a young reporter who came to interview her without having read her books to a New York cab driver who threw her out in a rainstorm after she demanded: “Are you incapable of keeping your mouth shut and just doing what you’re told?”

Boyers confesses to a sneaking admiration for that cabbie: “Few people were prepared to tell Susan to fuck off when she was behaving badly.” He wasn’t immune from such behavior himself. After decades of friendship, Sontag attacked him in front of a large audience for referring to her as “Susan” when introducing her. Steiner, too, could be cruel; when Boyers was a student in Steiner’s graduate seminar, his future friend mocked him in front of his classmates for not knowing German and taking the place of worthier students. Both condescended to him about his literary taste, with Sontag wondering how he could enjoy “the unspeakable Jay McInerney.” When Boyers pointed out that Sontag had never read McInerney’s novels, she replied, “Some writers you don’t have to read to know what they’re about.”

It goes without saying that Sontag and Steiner detested one another. One of the most wince-inducing scenes in Maestros & Monsters takes place on a bus to an academic conference, where Sontag kept saying hello to Steiner, louder and louder, as he stared out the window, refusing to answer. Boyers blames their falling out on Sontag’s failure to thank or repay Steiner after he obtained some rare books she asked for. But the whole episode sounds like it could have taken place in a kindergarten. Isaac Bashevis Singer once said that though he idolized Tolstoy, “The truth is if Tolstoy would live across the street, I wouldn’t go to see him,” and Boyers’s account of his idols’ bad behavior suggests the wisdom of this policy.

Such anecdotes make Boyers’s book delicious reading for connoisseurs of gossip about intellectuals. But this has never been a large group—“Now and then I find it necessary to remind myself that not everyone is apt to care as much as I do about George Steiner and Susan Sontag,” he writes in an afterword—and that group tends to shrink over time. Great novelists and poets can remain figures of fascination long after their deaths; there is no end to the writing of books about Marcel Proust and Virginia Woolf. Critics and intellectuals don’t inspire the same kind of loving devotion, which is only appropriate, since less love and generosity go into their work.

The more significant questions raised by Maestros & Monsters have to do with the intellectual style Sontag and Steiner adopted. This style—cosmopolitan, moralistic, fascinated by the intersection of literature and politics—was forged in the 1930s and 1940s by New York Jewish intellectuals such as Irving Howe, Clement Greenberg, and Lionel Trilling. According to Howe, these writers shared “a taste for the grand generalization, an impatience with what they regarded (often parochially) as parochial scholarship, an internationalist perspective.”

Whether these were virtues or vices—Howe himself seemed uncertain—they were traits that could only flourish outside the academy. Few of the New York intellectuals found jobs in universities until after World War II, when the barriers of genteel antisemitism started to crumble. (Trilling, who in the 1930s became the first Jew to achieve tenure in Columbia’s English department, was an exception.) Their preferred genre wasn’t the scholarly study but the freelance essay, published in little magazines like Partisan Review and Commentary that fostered intellectual chutzpah.

Sontag, too, held academia at bay; Boyers writes about his attempt to woo her to Skidmore College, which foundered on her recognition that she was not cut out to be a teacher. She published some of her best early essays in Partisan Review, including “Notes on Camp” (1964), a perfect example of the New York intellectuals’ brilliant eclecticism, which urged its readers to “Think of Bosch, Sade, Rimbaud, Jarry, Kafka, Artaud, think of most of the important works of art of the 20th century.” At the same time, Sontag thumbed her nose at the canon by intermingling references to King Kong, Jayne Mansfield, and the Beatles. In her famous first book, Against Interpretation (1965), she emerged as a champion of pleasure and play against the joyless hermeneutics of her elders. “Interpretation,” she famously declared, is “the revenge of the intellect upon art,” and it was as an aesthete and a hedonist that she captured the imagination of 1960s readers.

Yet Against Interpretation is itself a work of interpretation, an exceptionally cerebral one, and it didn’t take long for Sontag to emerge as a stalwart defender of the Trillingesque virtues of difficulty, irony, and moral earnestness. The title of her 1980 essay on Elias Canetti, “Mind as Passion,” expresses her own intellectual ideal as well: thinking is not an obstacle to feeling but the surest route to it. Like Canetti, too, she believed that “to think is to insist”—that is, to argue. Sontag was willing to trace this idea back to the European Jewish intellectuals she admired, but she had neither the knowledge nor the inclination to recognize its much deeper roots in Jewish interpretive tradition.

From beginning to end, Sontag’s essays were aimed at small audiences. (Boyers writes that she once suggested he review a certain book for Harper’s, the implication being that she herself would never stoop so low.) Steiner spent decades as a book critic for the New Yorker, but the critical persona he cultivated there, and in books such as After Babel and In Bluebeard’s Castle, was even more unremittingly highbrow than Sontag’s—perhaps to the point of vulgarity, as the critic James Wood charged in a devastating essay that Boyers spends several pages trying to refute.

Along with breadth of reference and brilliance in argument, Steiner won admiration for his staging of moral dramas, especially when writing about the Holocaust. “The world of Auschwitz lies outside speech as it lies outside reason,” he intoned in his 1967 book Language and Silence. “To speak of the unspeakable is to risk the survivance of language as creator and bearer of humane, rational truth.” Formulations like these made Steiner an emblem of what Sontag calls, in “Notes on Camp,” “Jewish moral seriousness.”

In defining their Jewishness in secular and literary terms, Steiner and Sontag were following a path long familiar to German Jewish intellectuals, from Heine and Marx to Walter Benjamin. In Europe, the intellectual vocation appealed to assimilated Jews who found themselves socially marginalized and spiritually homeless, because it turned these deficits into assets. The intellectual took pride in being what Hannah Arendt, another great example of the type, called a “pariah”: because he belonged nowhere, he could see the world truly, free from parochialism and self-interest.

But America was not Europe, and the New York Jewish intellectuals who started out in the 1930s as Marxist radicals soon had to rethink their calling in a society where the problem was not ostracism but acceptance—the temptation of disappearing into America’s mass culture and mass prosperity. When Sontag and Steiner emerged as intellectuals in the 1960s, they saw it as their duty to oppose these forces. In doing so, ironically, they earned greater fame and even wealth than earlier Jewish “pariahs” could have hoped for.

Their early lives were very different: Sontag was born in New York and raised in Los Angeles, while Steiner was raised in France until 1940, when his father managed to relocate the family to the US in the nick of time. But both studied at the University of Chicago, where they imbibed the idea of culture as a portable canon of Great Books, and both were drawn to Europe as a counterweight to American philistinism. Steiner went to Oxford for graduate study, taught at Cambridge, and spent twenty years at the University of Geneva, even as he maintained his American citizenship and wrote regularly for the New Yorker. For Sontag, living in Paris in the late 1950s was the beginning of a lifelong connection with European literary culture, and she played a key role in bringing the work of Roland Barthes, E. M. Cioran, W. G. Sebald, and many others to the US.

In turning or returning to Europe, Sontag and Steiner swam against the tide of American Jewish history. In the process they discarded some of the qualities that had made the New York intellectuals distinctively American—their allergy to pretension and their engagement with what Partisan Review famously called “our country and our culture.” Instead, Sontag and Steiner were drawn to the secular European Jewish tradition of allegiance to, in Steiner’s words, “our homeland, the text.” Part of this atavism was a resistance to the more positive forms of Jewish identity that appealed to American Jews in the later twentieth century, especially Zionism.

Another and perhaps more important part was the cult of Seriousness. Especially as they grew older, both Sontag and Steiner felt called upon not just to defend high culture but to incarnate it, which meant pretending to an omniscience and a moral solemnity that no individual could honestly sustain. The humorlessness, defensiveness, and insecurity that Boyers observed in both his friends can be diagnosed as symptoms of this lifelong strain. They weren’t just character flaws but intellectual ones—flaws in their idea of what it meant to be an intellectual. Reading Maestros & Monsters, it’s easy to feel that if that title is no longer as popular or prestigious as it used to be, perhaps it’s no bad thing. A writer is more honest, and ultimately more interesting, when he or she is not an intellectual but simply a person thinking.

Suggested Reading

George Lichtheim’s Marxmanship

The brief, wondrous life of a renegade intellectual.

New Thinkers, Old Stereotypes

Moshe Idel is heavy on melancholy, not to mention surprising claims about the scholars of Western Europe.

People of the Book World

"The Jewish market has become quite a good one,” a Knopf editor observed; even the “goy polloi” were buying, wrote another staffer.

Sundowning

In Morningstar Heights, Joshua Henkin tells his story simply and directly, with a narrative economy that conceals much close observation and human understanding. These have always been the strengths of his work, though they are not the qualities best rewarded in contemporary American fiction.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In